Home is Where the Heart Is

Jacqueline LeBlanc Cormier, Experience Congress 2011

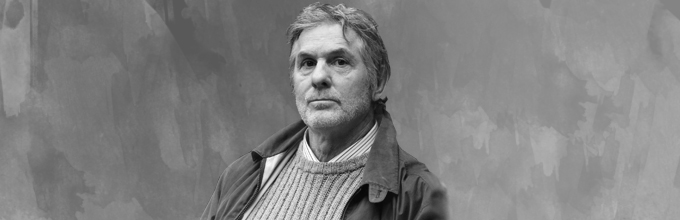

David Adams Richards certainly knows how to paint a picture.

A couple sits in an empty kitchen with nothing but a boiling kettle. Their children have been taken away by globalization.

Youth exodus and globalization are nothing new to the Maritime Provinces, let alone to Richards’ Miramichi.

In his Big Thinking lecture, Richards, who is known as one of Canada’s greatest place-based writers, spoke about the meaning of ‘local’ in a globalized world, asking whether place and communities are worth preserving.

The award-winning writer spoke to a packed auditorium on the St. Thomas University campus as part of the 2011 Congress of the Humanities and Social Sciences.

“This is a world that has faced globalization for years, and in each of my novels - the first written in 1974 - the young do leave because they have to,” he says. “These cultural, economic, and social disadvantages are not new to us. Global interests are in fact at the doorstep, buckled down with knives.”

Richards’ writing is full of a sense of place. He writes about the Miramichi, about the great river and the people who inhabit its coasts.

“I never knew I had a sense of place until people who reviewed books and who lived in cities told me I did,” he adds. “I simply wanted to tell the stories about the people I knew and grew up with. And I knew a great variety of people from all walks of life. But in telling these stories, you’d assume these people only came from this place, which in a way categorizes them as limited and not be able to cope with any other place.”

Although he now embraces his ‘sense of place,’ for years, he considered the critique as being ‘artistically derogatory.’

“It relies on this superior sense of cosmopolitanism,” he states. “The supposition came because of what qualified as a sense of place and that, because of this sense of place, one was often restricted.”

Despite some of his characters feeling trapped in their ‘place’ and having no option to change their fate, Richards believes there is always a choice to be free.

“Our place is, of course, not the south, or Cape Breton Island, or the Miramichi, or Saint John, or Fredericton, or the coal mines of England. But the human heart,” says Richards. “No moment or comfort is ever secure, no matter where we live. Our future is not certain for us no matter where we live. How we respond to this is up to us alone. Each one of us can choose to be free.”